Emily Dickinson Trail Guide

The Emily Dickinson Trail Guide and Trail Stations were funded in part by a grant from the Massachusetts Environmental Trust. These funds are made available to groups like ours by people like you that purchase any of the State’s 3 environmental license plates. We wish to thank the thousands of individual plate holders who voluntarily contribute their support to protect and preserve the waters and related resources of the Commonwealth and make projects like this possible.

For more information regarding the environmental license plate program, contact the Trust at www.mass.gov/eea/met or visit the Registry of Motor Vehicle’s web site to order a plate.

The Fort River Watershed Association would like to thank our project partners for making this trail guide possible:

“My River runs to thee” by Emily Dickinson

My River runs to thee –

Blue Sea – Wilt welcome me?

My River wait reply.

Oh Sea – look graciously!

I’ll fetch thee Brooks

From spotted nooks –

Say Sea – take Me?

Stop 1: Welcome to the Fort River Watershed

Stop 2: River Power

Stop 3: Beavers: River Engineers

Stop 4: Macroinvertebrates: River Critters

Stop 5: Migratory Swallows: Mosquito Eaters

Stop 6: Farming for a Healthy River

Stop 7: Migratory Fish: The Mighty Lamprey

Stop 8: Water Quality: Taking the Fort River’s Pulse

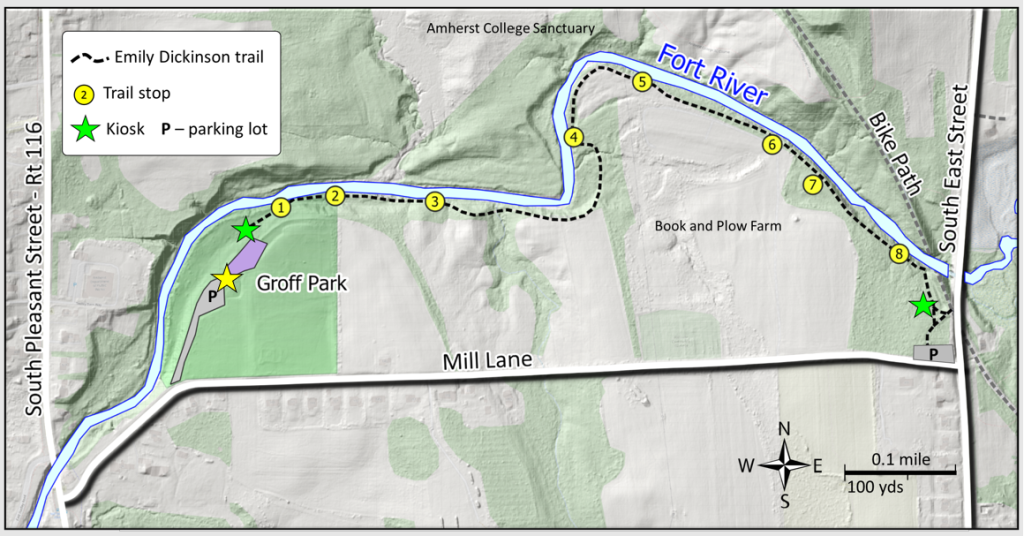

The Dickinson Trail (one of Amherst’s Literary Trails) gives one the opportunity to walk along the Fort River from Mill Lane, off South East Street to Groff Park. Originally the named Misty Bottom Trail, the trail stretches for 0.9 miles and is a relatively easy walk. The trail is marked with red blazes but there’s no getting lost as it twists along. There are three stream crossings, each with a named bridge (Rocky Top, Snake Point and Mice Hollow).

The river runs along most of the north side of the trail, with farmland, fields and woods to the south (part of the Amherst College conservation area). Given the mix of water, woods and fields birders can make good use of the trail as well. Much of the trail is shaded in summertime, colorful in the fall.

While some run the trail, its curves and bumps invite a slower walk, taking time to watch the river and listen to its flow. I find myself edging down toward the water, camera in hand, looking for reflections, ripples, play of the sunlight on the water. For me, the arc of the sun always brings a change in perspective and while early morning is a favorite time any other time will do. There’s not a lot of room on the trail but walkers always manage to make way for one another to keep a reasonable distance for passing or a conversation at a reasonable distance.

From the eastern (Mill Lane) end of the trail, you can access the Norwottuck Rail Trail, which leads to other town and Amherst College trails. The Groff Park entrance has more parking. The park has a picnic area, restrooms and a newly constructed playground, fully accessible, and splash pad.

A map of the Dickinson Trail and elevation is at: https://myhikes.org/trails/emily-dickinson-trail

The map indicates biking but note that the Dickinson Trail is not on the Town of Amherst’s list of trails approved for biking or horseback riding.

Photo and editorial credit: Bernie Kubiak, berniekubiak.zenfolio.co

Welcome to the Fort River Watershed

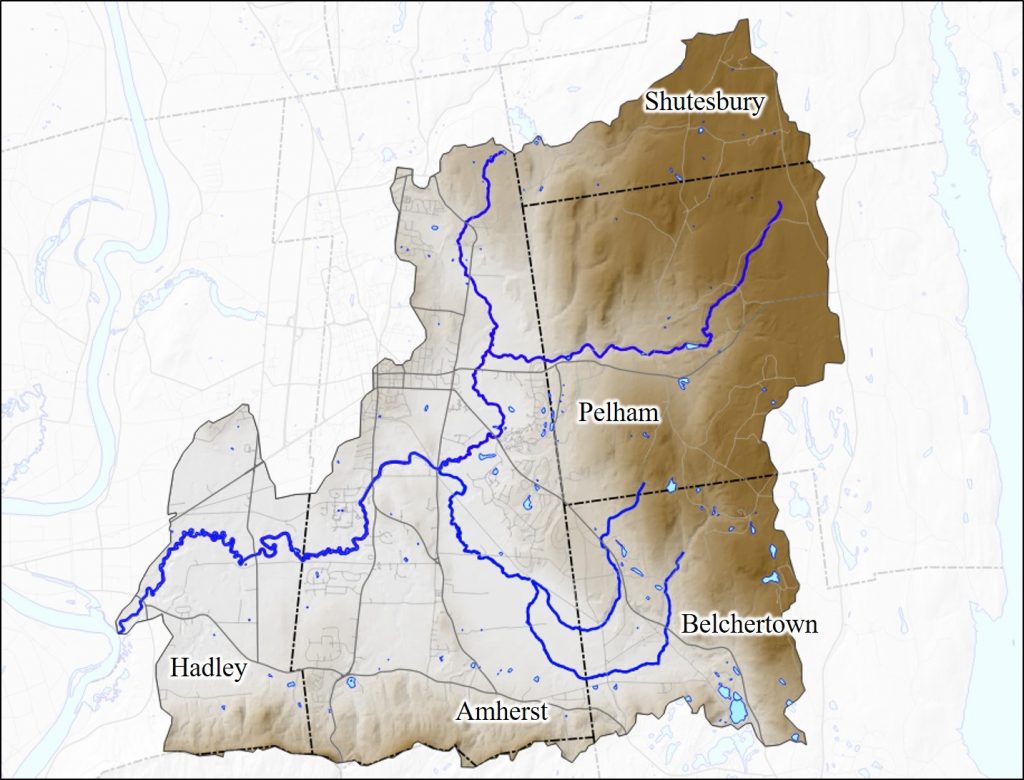

The term “watershed” refers to an area of land that empties all the water that flows over it into a body of water – a river, lake, or the ocean. The Fort River watershed collects the water from 35,000 acres across five towns.

Amherst and Hadley use the Fort River or its tributaries for their municipal water. The Fort River watershed is part of the much larger Connecticut River watershed, which drains much of Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Connecticut on its way to the Atlantic Ocean. The Connecticut River Conservancy and the Fort River Watershed Association work to protect these watersheds. US Fish and Wildlife maintains a series of preserves in the Connecticut River watershed (called the Silvio. O. Conte National Wildlife Refuge). Check out the Conte Refuge Fort River Division on Moody Bridge Road in Hadley.

Editorial credit: Dr. Brian Yellen

River Power

The Fort River is for most of its length a slow, meandering stream. The section in front of you is the only section having sufficient drop to be useful for waterpower. In 1756 eight men from Hadley signed a contract to operate a grist mill at the corner of what is now Mill Lane and Rt 116, with a sawmill added later, remaining in operation until 1938. The dam constructed with the mill changed the river from a free-flowing stream to a pond, stretching to what is now Groff Park and further. Closing the mill eliminated the need for the dam – the Fort River now has the distinction of being the longest undammed tributary of the Connecticut River.

Editorial credit: Bernie Kubiak, berniekubiak.zenfolio.co

Beavers: River Engineers

Did you know there are approximately 75,000 beavers living in Massachusetts? That’s just about the human population of Framingham; more than Holyoke and less than Springfield.

Beavers are keystone species: their dams create ponds and meadows that provide habitat for an entire food network of insects, fish, and birds. Beavers built a dam near this location in 2022. Attentive engineers, beavers do most of their construction and repair work at night to avoid predators. If a beaver thinks you are a predator, it may slap its tail on the water to warn you away. Unlike human built dams, migratory fish can easily pass through beaver dams, and may even enjoy a rest and a snack on the upstream side.

Editorial credit: Dr. Christine Hatch

Photo credit: Mark Lindhult

Macroinvertebrates: River Critters

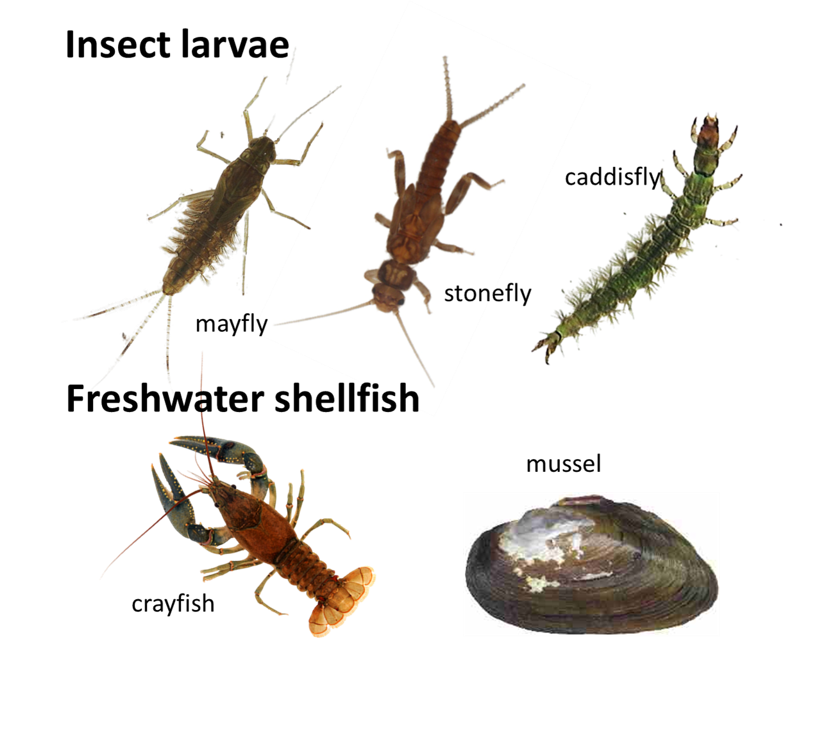

On the rocky stream bottom, you can spot many types of insects and other critters that lack bones that are referred to as macroinvertebrates. Examples include crayfish, mussels, and the larval stages of insects like dragonflies, which eat mosquitoes. These critters make up an important link in the food web.

Macroinvertebrates eat leaves and algae, and then become food for fish and birds. Cleaner streams have more and more different kinds of macroinvertebrates making these important animals living indicators of water-quality. They are sensitive to pollution, easy to study, and their long lifespan means that they indicate water quality over a period of time. Turn over a rock in the river and see if you can spot a macroinvertebrate! (Then please turn the rock back over carefully!).

Editorial credit: Dr. Brian Yellen

Migratory Swallows: Mosquito Eaters

Migratory tree swallows live and breed in open habitats along the Fort River and Emily Dickinson Trail in the spring and summer. They feed almost exclusively on insects, including flies, gnats, and mosquitoes. Thanks swallows! Sadly, tree swallows are in decline, likely due to a combination of climate change and habitat loss. Researchers at Amherst College have been studying the tree swallows next to the Fort River since 2004 using nest boxes. You might see one along the trail!

Editorial credit: Dr. Ethan Clotfelter

Farming for a Healthy River

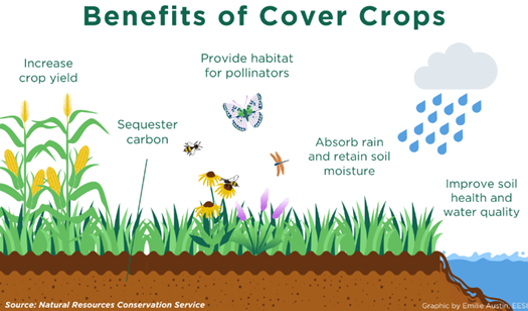

The fields of Amherst College’s Book and Plow Farm stretch out in front of you. The farmers here work in ways that are respectful of the Fort River ecosystem. For example, they rotate crops to reduce pest and disease pressure, and to minimize use of pesticides. They put down tarps to suppress weeds and prepare fields, while minimizing the use of heavy tractors that can compact the soil and lead to erosion. The farmers here also grow cover crops like clover or rye in fields that would otherwise be bare. These cover crops limit weeds, increase soil nutrients, provide habitat for birds and pollinating insects, and importantly, prevent erosion or soil run-off from our farm fields that could harm the Fort River.

Editorial credit: Maida Ives, Book and Plow Farm

Migratory Fish: The Mighty Lamprey

Many migratory fish visit the Fort River during their life cycle, traveling from up-river in the Connecticut River or down-river in Long Island Sound. Because the Fort River is undammed, migratory fish can access the excellent habitat of the Fort River for spawning. Salmon likely spawned in the Fort River during past centuries when Massachusetts was colder, but today the primary migratory fish is the lamprey. Lamprey are one of the world’s oldest fish species! Like salmon, adult lampreys live in the ocean and return to rocky rivers each June to lay eggs, and then die. After lamprey eggs hatch, the juveniles drift downstream to a sandy section of the river, where they will feed for three to four years by filtering the water. Then, when they have grown into adults they migrate to the Atlantic Ocean until they are ready to spawn.

Editorial credit: Dr. Brian Yellen

Water Quality: Taking the Fort River’s Pulse

Just like a nurse or doctor measures your vital signs – pulse, blood pressure, weight – scientists use certain measurements to gauge river health. Can you find the concrete platform in the river below you? The US Geological Survey measured river flow here from 1966 to 1996, which averaged about 40 cubic feet (300 gallons) per second. At the record high flow of 1,600 cubic feet per second, the river would fill a four-bedroom house with water in only ten seconds!

In addition to flow, the Fort River Watershed Association and the Connecticut River Conservancy also measure bacteria in the water, which can make rivers unhealthy for people and animals. The US Fish and Wildlife Service, the Town of Amherst and several conservation organizations also manage the public lands around the Fort River in order to protect and conserve its health and quality for people and wildlife.

Editorial credit: Dr. Brian Yellen